Making Fun: A Practical Design Toolkit for Building Games That Work: Discover the secret of making great and fun games

Great games are not accidents. They are deliberate constructions built from choices that shape what players feel, think, and do. This article lays out a compact toolkit for designing those experiences: how to stop aiming at a vague goal called fun and instead engineer specific emotional responses. It introduces two foundational frameworks that help match mechanics to player psychology and shows how to turn ideas into a shared, executable vision.

Key Takeaways

- “Fun” is too vague – Design for specific emotions and a defined audience, not a generic idea of fun.

- Bartle’s Taxonomy – Identify your core player type:

- Achievers (goals, mastery)

- Explorers (discovery, secrets)

- Socializers (community, collaboration)

- Killers (competition, dominance)

- MDA Framework – Connect mechanics (rules) → dynamics (player behaviors) → aesthetics (emotional responses).

- Eight Aesthetics – Target precise emotions:

- Sensation, Fantasy, Narrative, Challenge, Fellowship, Discovery, Expression, Submission.

- Game Design Document (GDD) – A living blueprint aligning the team on:

- Player profile

- Aesthetic goals

- Core mechanics

- Expected dynamics

- Success metrics

- Workflow – Choose an audience, prioritize 2–3 aesthetics, playtest, and iterate based on data.

- Avoid Pitfalls – Don’t try to please everyone; focus on your core audience and emotions.

Why “fun” needs to be replaced with precision

Designing for a generic idea of fun is like trying to build a house on fog. Players disagree about what is fun, and what delights one player may bore another. Instead of designing for everyone, the smarter approach is to design for someone. That means choosing an intended audience and defining the exact feelings the game should produce for them.

“Fun is just dangerously subjective.”

A compact toolkit helps transform subjective instincts into repeatable design decisions. Two tools stand out: a player classification system that makes the audience explicit and a design framework that connects code and rules to player emotion.

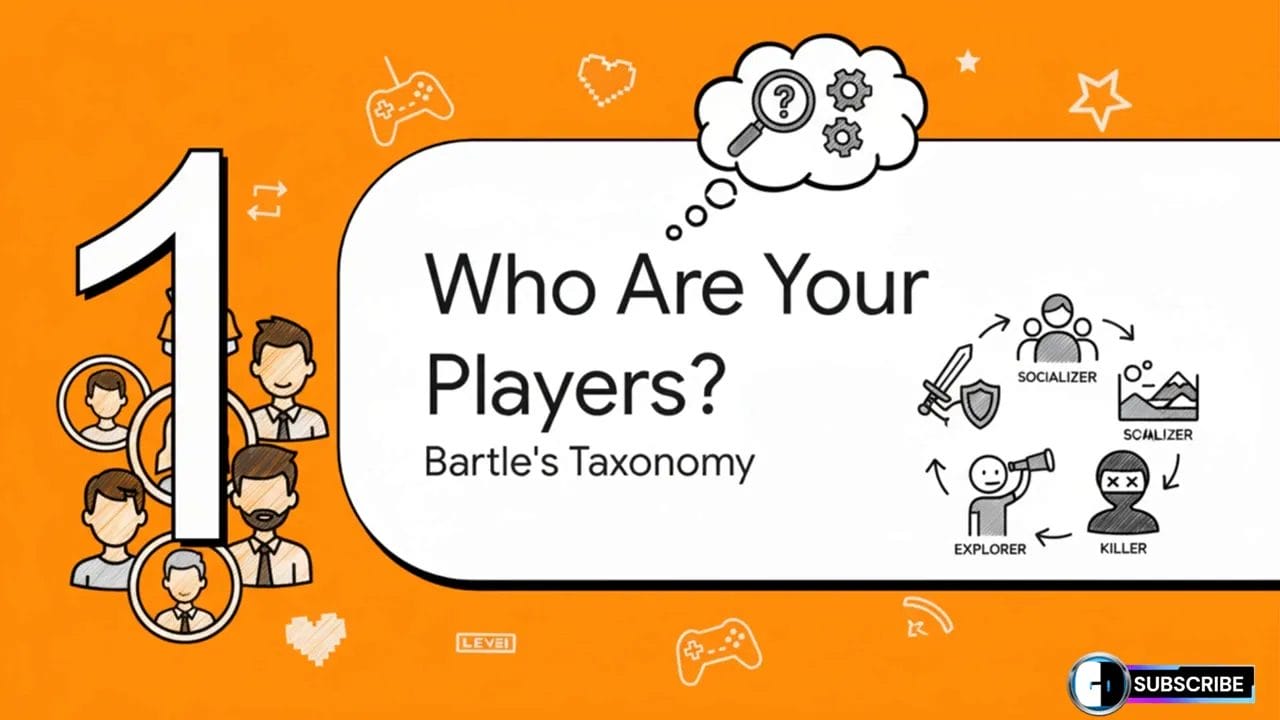

Design for someone: Bartle’s Taxonomy of player types

One of the earliest and most useful ways to think about players is to ask what they keep coming back to a game for. That question yields four archetypes that clarify motivations and priorities. Each type represents a different way of finding satisfaction in play.

Bartle’s taxonomy: the four player types that guide audience choices.

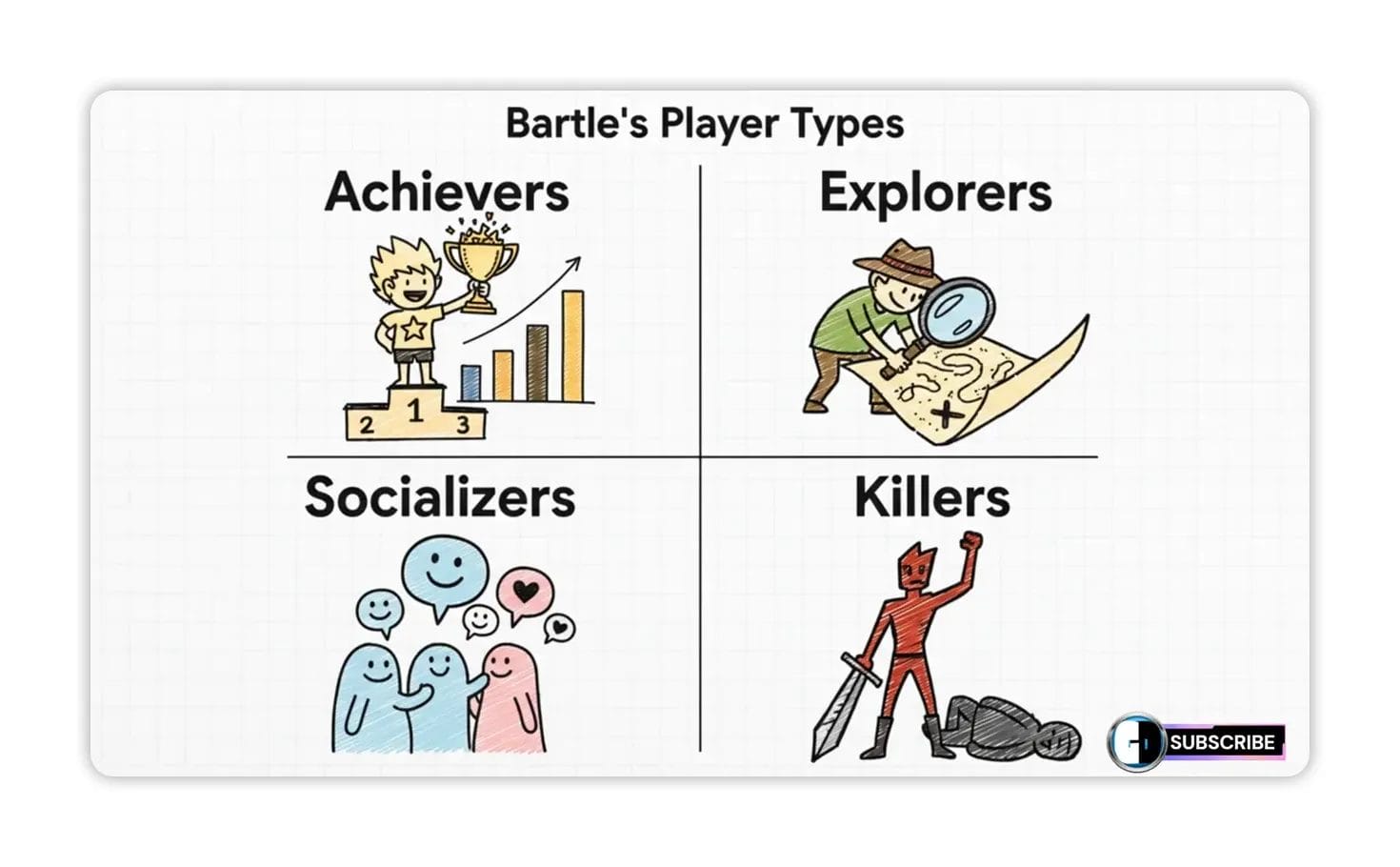

Achievers

Achievers pursue measurable goals: points, levels, collectibles, completion rates. The reward is mastery expressed as a metric. Features that appeal to achievers include progression systems, leaderboards, achievements, and clear, quantifiable objectives.

Explorers

Explorers play to learn how the world works. The joy comes from discovery, hidden systems, and emergent behavior. Open worlds, secrets, complex systems to probe, and tools for experimenting tend to engage this type.

Bartle’s player types quadrant — ideal for explaining target audiences.

Socializers

Socializers care about people. They find fun in conversation, collaboration, and community building. Chat systems, cooperative mechanics, social spaces, and features that encourage relationships are central to satisfying socializers.

Killers

Killers seek competition and dominance. They want to overcome other players and feel powerful doing it. Competitive ranking, PvP systems, asymmetric advantages, and opportunities to affect other players’ experiences draw in killers.

These four groups fall neatly on two axes: action versus interaction, and focus on world versus focus on players. Plotting these dimensions gives a clear visual that helps designers decide which player motivations their features should target. The taxonomy is especially useful when choosing what to prioritize; features that satisfy one type may alienate another, so trade-offs become explicit.

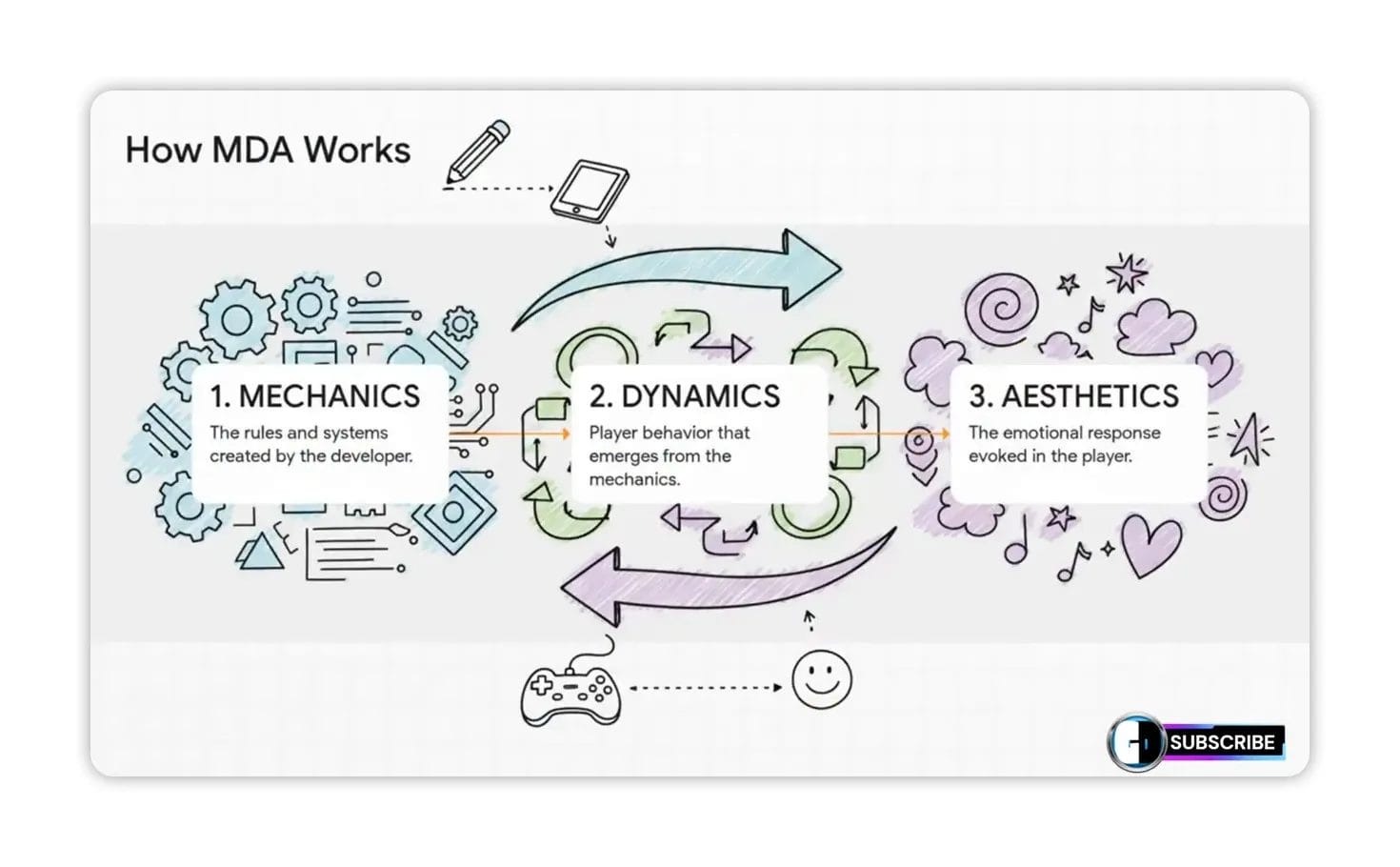

From rules to feeling: the MDA framework

Once the audience is chosen, the next problem is mapping design work to emotional outcomes. That’s where the MDA framework — Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics — comes in. It creates a bridge between what developers implement and what players experience.

Diagram showing how mechanics produce dynamics which create aesthetics.

Mechanics

Mechanics are the concrete rules and systems: the code, parameters, and formal constraints that define what is possible in the game. Mechanics are what the team builds.

Dynamics

Dynamics emerge when players interact with mechanics. They are the run-time behaviors, strategies, and patterns that arise during play. Dynamics are often visible only in testing and through player interactions.

Aesthetics

Aesthetics are the emotional responses the game produces. They describe what the player feels: excitement, curiosity, relaxation, or the thrill of mastery. Designers create mechanics in hopes of shaping dynamics that produce desired aesthetics.

Designers work from mechanics up to aesthetics, while players experience aesthetics first and trace them back. That mismatch makes it crucial to be deliberate about which aesthetics the mechanics are intended to produce.

The eight aesthetics of play: a usable vocabulary for “fun”

Aesthetics can feel fuzzy unless they are named and defined. The “eight kinds of fun” provide a clear vocabulary for targeting precise feelings. Instead of promising fun, a designer can aim for challenge, discovery, or fellowship. Below are the eight aesthetics with practical notes on what mechanics typically produce them.

Sensation

Sensation is pure sensory pleasure: sights, sounds, haptic feedback, and tactile responsiveness. Fast, responsive controls, crisp audio cues, impactful visual effects, and physical feedback create sensation.

Sensation: sight, sound and touch working together.

Fantasy

Fantasy is the pleasure of role and make-believe. Immersive worldbuilding, believable NPCs, character abilities that deviate from reality, and strong thematic design enable players to step into different roles.

Fantasy — the imagined world seen through the player’s headset.

Narrative

Narrative is story-driven engagement: characters, plot, choices with consequences. Branching dialogue, emergent story moments, and clear narrative stakes anchor this aesthetic.

Narrative — sequencing events to create player story.

Challenge

Challenge is the satisfaction of overcoming skillful obstacles. Carefully tuned difficulty curves, tight controls, and systems that reward mastery produce meaningful challenge and triumphant moments.

Challenge — overcoming obstacles on the way to a trophy.

Fellowship

Fellowship is the feeling of belonging and teamwork. Mechanics that encourage cooperation, shared goals, guilds, and social tooling support fellowship.

Fellowship — teammates celebrating a shared win.

Discovery

Discovery hits curiosity. It arises from non-obvious systems, hidden areas, procedural surprises, and rewards for exploration. Players who love discovery need systems that contain secrets to reveal.

Discovery — revealing secrets on the map with a lantern.

Expression

Expression is identity and creativity. Building tools that allow personalization, creation, or unique playstyles encourages players to leave a personal mark on the world.

Expression — avatar parts and tools for personalizing play.

Submission

Submission is the soothing pacing of low-effort, high-reward activities. It is the meditative pleasure of repetitive tasks done well. Systems that support flow), routine, and small, reliable rewards foster submission.

Submission — tending plants as a soothing, repetitive activity.

Putting the pieces together: design as engineering

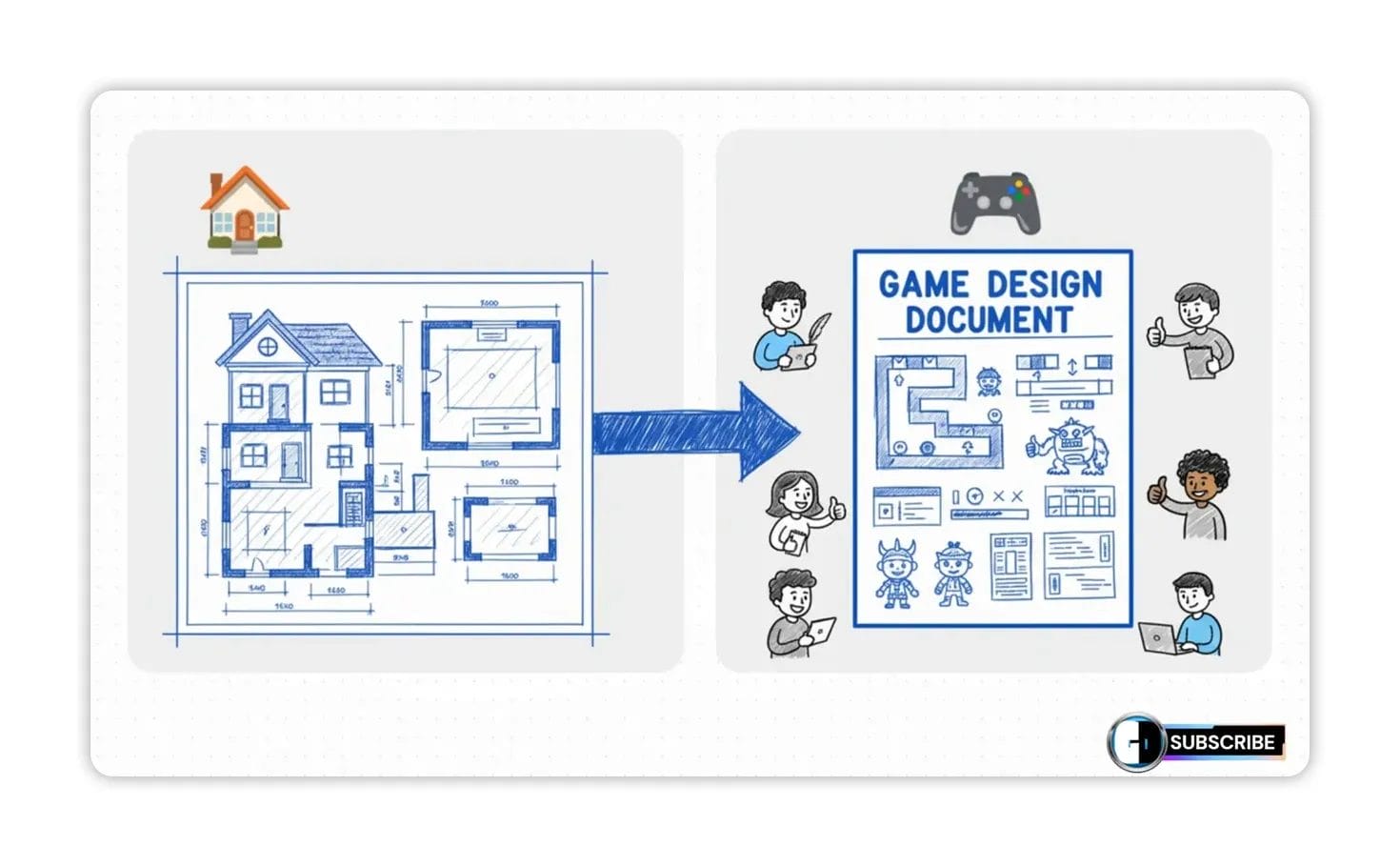

With a clarified audience and a vocabulary for emotion, the final challenge is coordination. Teams with artists, programmers, writers, and designers all must build the same game. That requires a single source of truth: the game design document.

Game Design Document as the blueprint for production — clear and legible.

The GDD is more than a wishlist. It is a blueprint that explains which player types the game targets, which aesthetics the team must produce, and which mechanics are expected to create the right dynamics. Without that clarity, a brilliant idea remains an unrealized vision.

What a good GDD contains

- Player profile — which of Bartle’s types are primary and secondary targets.

- Aesthetic goals — which of the eight aesthetics the experience should evoke, prioritized and explained.

- Core mechanics — a concise, testable description of the systems and rules.

- Expected dynamics — predicted player behaviors and emergent interactions to watch for in playtests.

- Success metrics — concrete signals that the intended aesthetics are being achieved, such as engagement patterns or retention split by player type.

- Art and audio briefs — how presentation supports the targeted aesthetics, especially for sensation and fantasy.

Practical workflow: how to use these tools day to day

The frameworks become powerful when embedded in development cycles. Here are practical steps teams can adopt.

- Choose a primary player archetype. Decide who the game is for early, then vet major features against that archetype.

- Pick two or three target aesthetics. Prioritizing prevents feature creep and mixed signals that dilute emotional impact.

- Translate aesthetics into mechanics. For example, if discovery is a target aesthetic, invest in systemic depth and hidden states rather than surface-level collectibles.

- Document expected dynamics. Before implementation, hypothesize how players will use systems and write those expectations in the GDD.

- Playtest with purpose. Run tests that measure the predicted dynamics and observe whether they produce the intended aesthetics.

- Iterate deliberately. Use data and observation to tune mechanics so dynamics shift in the desired direction.

Examples: mapping goals to design choices

Small examples show how these frameworks guide decisions.

Example 1 — A co-op dungeon crawler aimed at fellowship and challenge

Target players: Socializers and Achievers. Aesthetic goals: fellowship and challenge. Mechanics: roles with complementary abilities, shared objectives, and a revive mechanic that reinforces teamwork. Expected dynamics: players coordinate responsibilities, trade resources, and develop informal strategies around role synergies. Playtests focus on whether teams communicate and whether success feels tied to cooperation rather than individual skill.

Example 2 — An open-world exploration game aimed at explorers

Target players: Explorers primarily. Aesthetic goals: discovery and fantasy. Mechanics: layered world systems, environmental storytelling, and tools that let players probe systems (like scanning or mapping). Expected dynamics: players experiment, catalog findings, and form personal theories about hidden rules. Success is measured by time spent in unmarked areas and frequency of player-created guides or maps.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Trying to please everyone. Mixing too many primary aesthetics diffuses the experience. Pick audience and feeling first, then prune features that conflict.

- Confusing mechanics with experiences. Building a flashy mechanic does not guarantee the targeted aesthetic. Observe player behavior and iterate until the dynamics line up.

- Keeping the GDD static. Treat the GDD as a living document that evolves with playtest findings and production constraints.

Design as responsibility

Good design is a promise to the player. That promise says: “If you spend time here, you will feel X.” Bartle’s taxonomy helps define who is being promised that experience. The MDA framework and the eight aesthetics help specify what X should be. The GDD ensures everyone on the team is accountable for delivering that promise.

At the end of the day, an idea that cannot be executed is worthless. The final product a player holds is what matters, not the perfect image in a designer’s head. Using these tools turns guesswork into engineering. The only remaining question is which deliberate experience the team will choose to build.

A direct prompt: which experience will you build?

FAQ

How does Bartle’s Taxonomy apply to single-player games?

Bartle’s framework centers on motivations rather than multiplayer mechanics. Single-player games can still target Achievers with progression systems, Explorers with rich environments and secrets, Socializers by designing NPC relationships and community tools like leaderboards or shared spaces, and Killers by including competitive leaderboards or asynchronous PvP. The taxonomy helps prioritize which motivations the game supports.

What is the difference between mechanics and dynamics?

Mechanics are the formal rules and systems implemented in the code. Dynamics are the patterns and behaviors that arise when players interact with those mechanics. Mechanics are designed; dynamics are observed during play. Designers should predict dynamics and test whether they appear as intended.

Can a game target more than one aesthetic?

Yes, but prioritization is important. Targeting too many core aesthetics often leads to diluted experiences. Many successful games focus on two or three complementary aesthetics and support a broader set of secondary pleasures.

What should be included in a Game Design Document?

A useful GDD includes the target player profile, prioritized aesthetic goals, core mechanics, expected dynamics, success metrics, and presentation briefs. It should make clear why each feature exists and how it contributes to the targeted player experience.

How do designers measure whether the intended aesthetics are working?

Use a combination of qualitative observation and quantitative metrics. Look for play patterns that indicate desired dynamics, collect player feedback on feelings, and measure engagement signals such as time in certain systems, completion rates, and retention segmented by player type.

Game Developer | Designer | Creative Storyteller

Matt Dogherby is a passionate game developer and designer based in Brisbane, Australia. With a career spanning over 15 years, Matt combines technical skill with a deep love for storytelling to create games that captivate and inspire. His unique perspective is shaped by the laid-back energy of Brisbane and his lifelong connection to the ocean, where he often trades coding sessions for surf sessions.